Introduction:

whales are considered the largest animals in the history of the planet. From July to October, the gentle giants can be found in the Santa Barbara Channel, where nearly 2,000 whales travel out to sea to forage on their own. Despite their enormous size, whales feed on small shrimp-like crustaceans called krill, eating up to 40 million krill per day.

From land to sea:

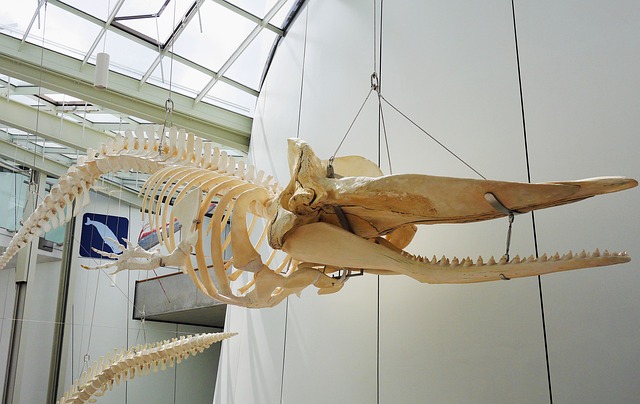

The skeleton is simple and light because it no longer needs to support the body mass in the water. The spongy bones, covered with a thin layer of compact bone, have very fatty bone marrow and historically accounted for a third of the amount of oil harvested by whales.

Head and Teeth

In the course of evolution, the two nostrils were moved to the top of the skull. While baleen whales have two blowholes, toothed whales only have one on the surface of their skin. Once they reach the surface, whales breathe in without having to move their heads. The nose was also extended and became a stage. Most toothed whales have identical, cone-shaped teeth that they use to capture and break down their prey, while their stomachs do all the digestion. The porpoise has spade-shaped teeth.

Spine:

The spine is long and rather stiff. Most whales’ necks have shortened and lost much of their mobility. The seven cervical vertebrae are compressed and sometimes fused to stabilize the head in the water and reduce energy expenditure. Vertebrae in rorquals are free and separate, except fin whales, whose 2nd and 3rd vertebrae are partially fused. Belugas, narwhals, and freshwater dolphins have retained some flexibility and can turn their heads slightly. Thoracic and lumbar movement is quite limited. A vertebra acts as a pivot point in the tail area, providing sufficient flexibility for complex and powerful movements of this horizontal fin, which acts as propulsion.

Limbs:

The front legs of the whales’ nomadic ancestors became much shorter and turned into pectoral fins. The legs are no longer mobile and allow no movement. The only point of articulation is the shoulder. These fins act as stabilizers and rudders. Five digits for toothed whales and cetaceans, four for giant whales: some are very long and have many more phalanges than land mammals. The bones of the hand are embedded in fibrous, stiff, and resilient tissue and are not visible on the surface of the skin. The whales are missing their back legs. The pelvis is represented by two small, free-floating, rudimentary bones that serve as a framework for the male genitalia and as an attachment point for the penile muscles.

To dig deeper:

Visit the Marine Mammal Interpretation Center (CIMM) in Tadoussac and its large collection of skeletons.

There are a few things to keep in mind when it comes to whale skeletons.

When a whale carcass washes up or a whale dies on the beach, there are a few things we need to consider before re-articulating (or reassembling) the skeleton for display.

We are checking:

carcass condition;

location of the carcass;

Is it a rare species that has limited (or no) representation in public displays?

Is there an important conservation or biology lesson to be taught?

Metamorphosed whale skeletons have enormous educational and scientific value.

They provide the opportunity to study the evolution, comparative anatomy, and bone diseases of these animals.

The position, shape, and number of teeth vary greatly between species.

Observers will notice that the fins have similar bones (humerus, radius, ulna, toe-shaped phalanges) found in other mammals, including humans.

In some skeletal images, we see signs of injury, disease, healing, and aging.

Skeletal displays also aid in the behavioral interpretation of observations in the wild. For example, a whale’s physical limitations are often not apparent in nature, but understanding these limitations through skeletal studies helps us understand the connections between biology, anatomy, and behavior.

SKELETON OF THE DEEP:

Jacobs Family Gallery and Dr. Roderick H. Turner Gallery

Continuous exhibition

The New Bedford Whaling Museum is home to four large whale skeletons and one very special small skeleton. This page links you to four more pages, each focused on a specific species.

The skeletons shown are from animals that died accidentally or due to unknown circumstances. Although New Bedford has been known for its whaling for almost two centuries, we did not hunt any of the animals on display in the museum.

Skeletons are important teaching aids for museums, science centers, and aquariums. The size of the skeletons inspires awe and conveys a greater appreciation for their mobility. Looking at the structure of the skeleton allows for lessons in comparative anatomy and can build a more personal connection with our mammalian brethren. The presence of these specimens raises questions among staff and volunteers, which then leads to a better understanding of these animals and their natural history. Researchers who study the condition of these bones can obtain information about the animal’s health shortly before its death.

One of only five complete blue whale skeletons in the United States

CONTINUOUSLY:

Some natural history museums have iconic dinosaur skeletons. We have a skeleton of the largest animal that ever lived on earth: the blue whale.

One of only five complete blue whale skeletons in the United States, the museum’s iconic 70-foot-long phenomenal specimen is more than just a well-known Santa Barbara landmark. In addition, it offers children and adults a rare opportunity to learn about and appreciate the world’s largest animals.

The nearly 7,700-pound skeleton is made of 98% real bone and consists of four specimens. The skull, mandibles, and one of the ear bones came from two different blue whales that beached in Ventura, California in September 2007; The last five tail vertebrae are cast replicas of the blue whale tail vertebra on loan from the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, and most of the skeleton comes from a blue whale beached at South Vandenberg Air Force Base in 1980.

Despite their enormous size, whales feed on small shrimp-like crustaceans called krill, eating up to 40 million krill per day.