Introduction:

The turtle skeleton system is a remarkable structure that serves as the framework for these fascinating reptiles, providing support, protection, and mobility. Turtles belong to the class Reptilia and are known for their distinctive hard shells, which are an integral part of their skeletal system. This intricate framework not only offers a unique defensive mechanism but also plays a crucial role in the overall physiology and behavior of turtles. Exploring the turtle skeleton system unveils a fascinating blend of adaptation and evolution that has allowed these creatures to thrive in diverse environments around the world. In this introduction, we will delve into the key features of the turtle skeletal system, examining its composition, functions, and the evolutionary significance that has shaped these ancient reptiles into the resilient and intriguing beings we observe today

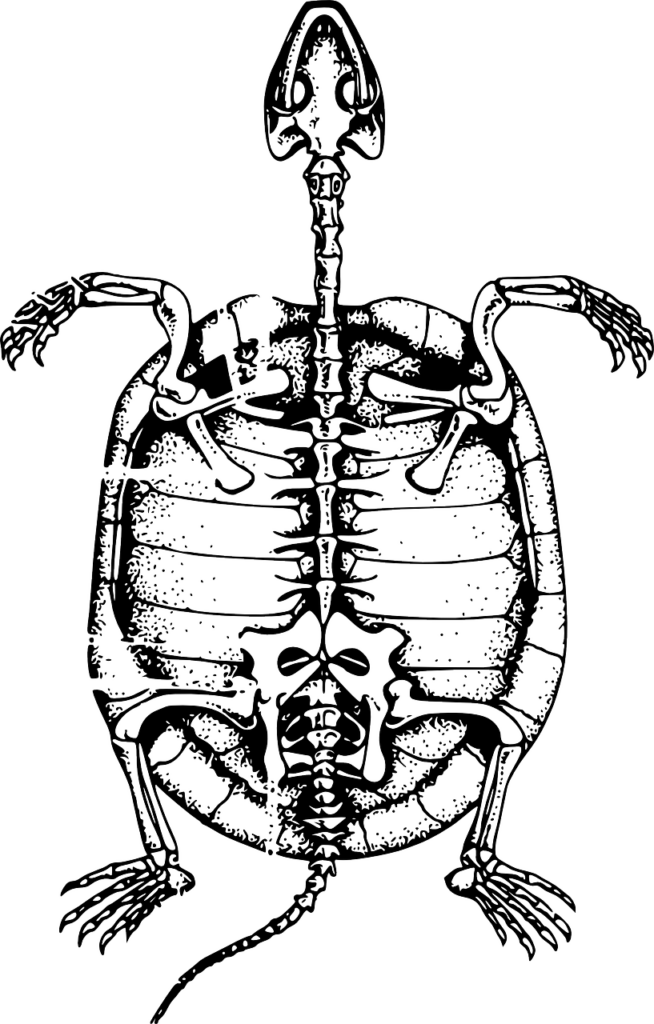

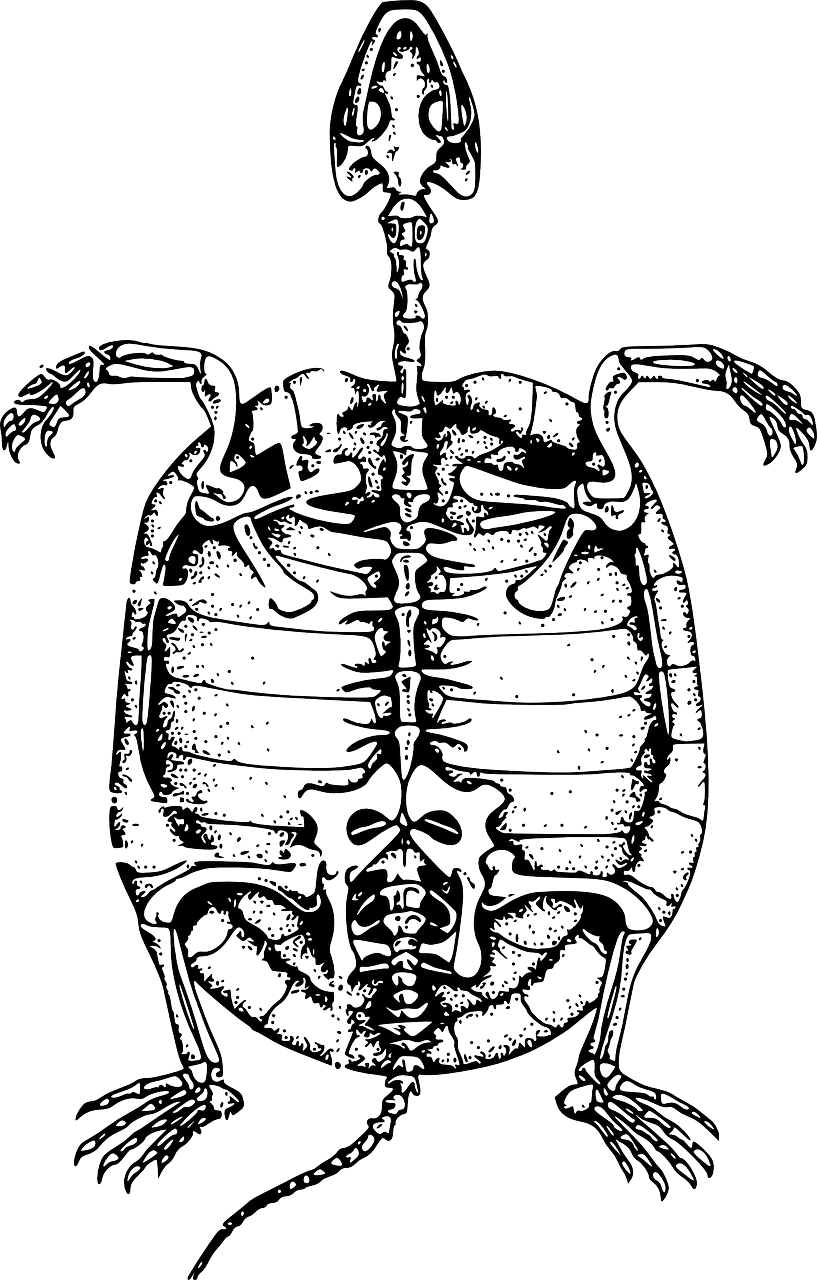

A skeleton of a turtle:

A reptile with an oval shell and horn beak. A turtle has a very short tail and four small legs and moves very slowly.

Skull: Bony shell of the turtle’s brain.

Phalanges: Small bones that form the fingers.

Humerus: Arm bone.

Proscapular process: Bone of the pectoral girdle of a turtle, located in front of the coracoid.

Spine: the backbone of a turtle.

Femur: Femur.

Tibia: Either two leg bones.

Phalanges: Small bones that form the toes.

Fibula: Either two leg bones.

Pelvic Girdle: Group of bones to which a turtle’s limbs are attached.

Coracoid: bone in the pectoral girdle of a turtle.

Scapula: shoulder bone.

Radius: both bones of the forearm.

Ulna: both bones of the forearm.

Vertebrae: All the bones that make up a turtle’s spine.

Mandible: The lower jaw of the turtle.

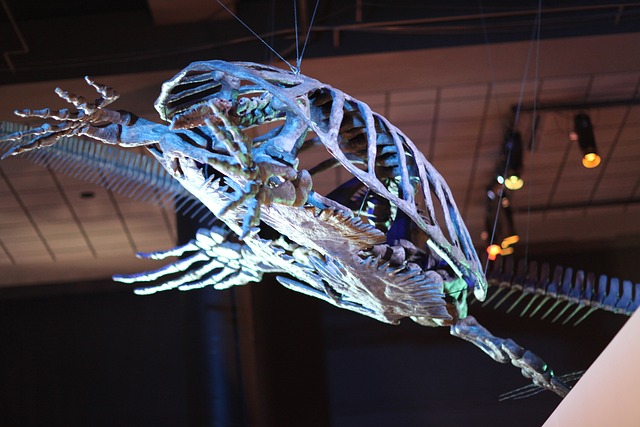

How the turtle got its shell through skeletal displacement and muscle origami:

The turtle’s shell provides it with formidable defenses that are unique in the animal world. No other animal has a similar structure, and the turtle’s bizarre anatomy extends to the skeleton and muscles contained within its bony shell.

The shell itself consists of widened and flattened ribs that are fused with parts of the turtle’s spine (so unlike in cartoons, you can’t pull a turtle out of its shell). The shoulder blades lie beneath this bony shell and are actually in the turtle’s ribcage, for all other animals with a backbone, whose shoulder blades sit outside the ribs (think of your own back first). The turtle’s trunk muscles are arranged even more bizarrely.

This body plan—and especially the odd position of the shoulder blades—is so radically different from all other vertebrates that biologists have difficulty explaining how it might have gradually evolved from the standard model, or what the intermediate ancestors might be. have looked. Enter Hiroshi Nagashima of the RIKEN Center. He has found some answers by studying how Chinese softshell turtle (Pelodiscus sinensis) embryos change from the standard body size of other vertebrates to the bizarre configuration of adult turtles.

By comparing the embryos with those from mice and chickens, Nagashima showed that all three species start with a common pattern that their most recent common ancestor probably also had. Only later does the turtle do something different, starting with a series of muscular origami movements that deform its body design into the adult version.

The embryos of all three species initially have scapulae that sit outside the ribs. In mice and chickens, the blade begins to grow backward and extends along the trunk over the developing ribs. The ribs themselves extend along the flanks of the embryos and are surrounded by a layer of muscle called the muscle plate (or myotome). These elements – ribs, shoulder blades, and muscle plate – remain largely the same shape as the animals mature.

In turtles, early embryos have the same ground plan as mice and chickens, but there are subtle differences. The shoulder blade is further forward and the ribs themselves are much shorter and never extend into the flanks of the embryo. As it grows, things change hysterically.

The muscle plate in the lower half of the turtle’s body folds inward along a line that runs the length of the turtle’s body. This line ultimately forms the edge of the carapace and is called the carapace edge. Meanwhile, the second pair of ribs (r2 in the image below) grow outward and swing forward over the shoulder blade (fm in the image below). Something similar happens with the animal’s hips. These two crucial events—the folding of the muscle plate and the growth of the other ribs—bring the scapula within the confines of the ribcage. Both steps are possible because the turtle’s ribs stop growing early in its development and no one yet knows why this happens.

The muscle that connects the scapula to the second pair of ribs – the serratus anterior – is twisted but retains its original connection to both bones (see above). Other muscles, especially those that move the limbs, form completely different connections.

In mice and chickens, the large latissimus dorsi muscle (which connects the top of the forearm to the back) initially grows from the limb bud of the embryo, attaches to the trunk, and begins to extend backward to cover the back. In the turtle embryo, the developing muscle attaches to the front of the developing shell near the neck. Similarly, the pectoral or pectoral muscles of chickens and mice grow from the limbs to the sternum, while those of turtles are connected to the plastron – the lower half of the shell. These new connections explain the bizarre differences between the muscles of adult turtles and other vertebrates.

Nagashima also points out that his findings secure the place of a recently discovered fossil turtle – Odontochelys – as an intermediate form between turtleless turtles and modern versions. Odontochelys was a hemicephalic turtle whose shell had a lower half (a plastron) but no upper half (a carapace). The discoverers suggested that this was a sign that turtles had evolved from a half-shelled form, but other researchers argued that it could just as well be a descendant of full-scaled turtles, which themselves had lost half of their shells.

Odontochelys also had short ribs on its back that had apparently stopped growing prematurely. But his second set of ribs was never large enough to cover his shoulder blades, which were still in front of his entire ribcage. This is consistent with the body structure of modern turtle embryos in the early stages of development and supports the idea that this extinct turtle was an ancestor. See more

FAQS:

All turtles have a unique body plan: an autapomorphic carapace on the dorsal side that contains dorsal ribs and carapacial bony plates, and a ventral shell of intramembranous bones that form a Chelonia-specific plastron. The dorsal and ventral shells develop as separate and different entities in turtles.

They’re also some of the only animals that can breathe. With their butts.

Just like humans, turtles also have various organ systems to keep them alive; such as the skeletal system, circulatory system, excretory system, reproductive system, respiratory system, digestive system, and nervous system.

Flexi Says: Turtles have an endoskeleton, which includes their backbone and ribcage.